Michael Roberts Marx and Engels are often accused of a “Promethean” vision of human social organization — namely that human beings, using knowledge and technical prowess, can and should impose their will on the planet and what is called “nature” — for better or worse.

Engels attacked the view that ‘human nature’ is inherently selfish and will just destroy nature. He described that argument as a ‘repulsive blasphemy against man and nature.’

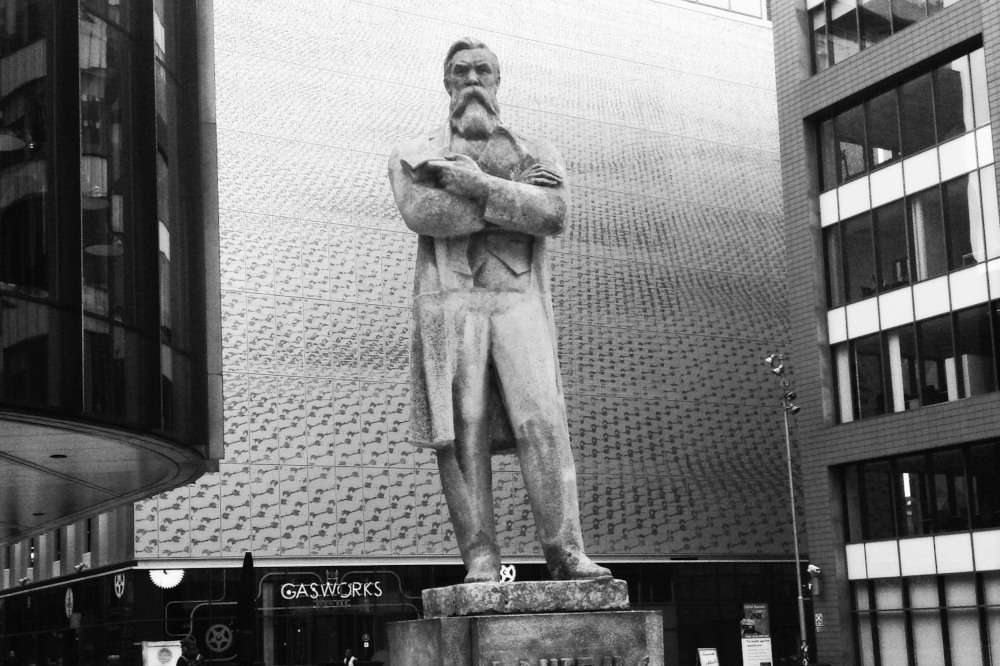

This charge is particularly aimed at Engels who, it is claimed, took a bourgeois “positivist” view of science: scientific knowledge was progressive and neutral in ideology, and so was the relationship between man and nature. Indeed, the modern “green” critique of Marx and Engels is that they were unaware that homo sapiens were destroying the planet and thus themselves. Instead, Marx and Engels had a touching Promethean faith in capitalism’s ability to develop the productive forces and technology to overcome any risks to the planet and nature.

But in truth, Engels was ahead of Marx (yet again) in connecting the destruction and damage to the environment that industrialization was causing. While still living in his hometown of Barmen (now Wuppertal), at the age of eighteen, he wrote several diary notes about the inequality of rich and poor, the pious hypocrisy of the church preachers, and also the pollution of the rivers.

In Umrisse, Engels noted how the private ownership of the land, the drive for profit, and the degradation of nature go hand in hand. Once the earth becomes commodified by capital, it is subject to just as much degradation as labor. We now know that COVID-19 and other pathogen pandemics are due to capitalism’s drive to industrialize agriculture and usurp the remaining wilderness that has led to nature “striking back,” as humans come into contact with pathogens to which they have no immunity.

So, at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is worth returning to one of Engels’s great works: The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man. In this unfinished piece, Engels shows the intimate connection between human labor and nature — a connection that if disrupted would devastating to humanity as well as to the other species of the planet. For him,

at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature like a conqueror over a foreign people, like someone standing outside nature — but that we, with flesh, blood and brain, belong to nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.

Engels attacked the view that “human nature” is inherently selfish and will just destroy nature. He described that argument as a “repulsive blasphemy against man and nature.” Humans can work in harmony with and as part of nature. It requires greater knowledge of the consequences of human action. But as Engels said: “To carry out this control requires something more than mere knowledge.” Science is not enough. “It requires a complete revolution in our hitherto existing mode of production, and with it of our whole contemporary social order.” The “positivist” Engels, it seems, still supported Marx’s materialist conception of history.